Book Review – NANCY CUNARD: PERFECT STRANGER by Jane Marcus

how to join

Resources

about ccwh

We help women historians thrive through events, resources, and community.

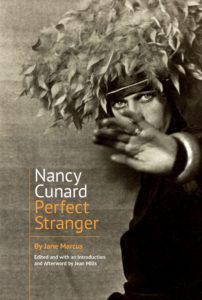

Jane Marcus, Nancy Cunard: Perfect Stranger. Edited with an introduction and afterword by Jean Mills. Clemson University Press, 2020. 256 pp.

Reviewed by Sandi E. Cooper

One lasting impact of the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s has been the dramatic expansion of what history, literature, and other disciplines consider worthy of exploration. Much of that transformation came from younger women scholars who stubbornly unearthed the missing and the silenced. Jane Marcus (1938-2015), distinguished professor at the City University of New York, was among the most gifted of those pathbreakers. She confronted and overturned the accepted canon with her work on Virginia Woolf, her discovery of women modernists and political radicals of the interwar decades, and her remarkable presentation of the maverick English heiress, Nancy Cunard (1896-1965). Marcus died before her Cunard study was polished for publication – a task completed by her former student and now established literary scholar, Jean Mills, Professor of English at John Jay College-CUNY. Mills uncovered notes, computer files, scribbles, and hints left by Marcus to assemble this unusual presentation of Nancy Cunard’s stunning bohemian creativity.

Marcus did not intend a chronological biography but rather a critical dissection of Cunard’s widely variegated cultural products. She begins with Cunard’s confrontation with the prevailing post-World War I male modernists, notably T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound – both right-wingers. (Pound’s support of Italian Fascism earned him a US prison term after the Second World War.) Along the way, Cunard broke with her mother, who was a patron of arts, opera, and eminent London names. After leaving England for Paris, Cunard learned the French language and in 1928 she set up her own press, the Hours, for which she taught herself typesetting. She discovered the writer Samuel Beckett and was the first to publish his works. Cunard enjoyed a long list of lovers including the surrealist Louis Aragon; adored jazz and fell deeply in love with everything and anything African – from the arts of the continent to the culture imported from Black America to Paris. Her politics moved farther and farther left; she became a journalist and eventually covered the Spanish Civil War. As a journalist, Cunard broke conventions (as does Jane Marcus) writing in the first person and asserting herself; the “I” becomes a legitimate authority, an honest assertion of belief replacing the presumed neutral third person singular.

Cunard’s gut hatred of England and of the Catholicism in which she was raised led her to reject all conventions – literary, cultural, sexual. Paris was fertile ground to nurture American jazz, Black musicians, jitterbug dancing, and Henry Crowder, who became her lover and she, perhaps, his muse. In her large property in Normandy, the rooms were filled with African art – many of the works destroyed by Nazi occupiers who viewed that genre as degenerate. (She escaped before they arrived.) Cunard was famous for wearing an arm full of African bracelets in gold, silver, and ivory. Mills includes a wonderful photo taken by Man Ray, highlighting the bracelets.

Perhaps her most significant, long-lasting gift to the generations was Negro Anthology. In this huge volume, Cunard assembled and published works from all sites of Black production – from across Africa, as well as the West Indies, Harlem, France, and parts of South America. Poetry, prose, music, history, art, and sculpture were all presented in this magnum opus to demonstrate the genius of African-based creators. Before she died, Marcus repeatedly talked about finding some way to reprint this extraordinary work that truly belongs as part of the canon.

This is not a biography of Cunard. Editor Jean Mills points to works by Anne Chisholm and Hugh Ford for a chronological presentation of Cunard’s life. Instead, Marcus’ contribution clarifies the significance of Cunard’s seemingly chaotic life and work to both modernism and Black culture.

September 22, 2021

how to join

Resources

about ccwh

We help women historians thrive through events, resources, and community.

Copyright © 2022 Coordinating Council for Women in History. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | site credit