Book review – MADAM C.J. WALKER’S GOSPEL OF GIVING: BLACK WOMEN’S PHILANTHROPY DURING JIM CROW by Tyrone McKinley Freeman

how to join

Resources

about ccwh

We help women historians thrive through events, resources, and community.

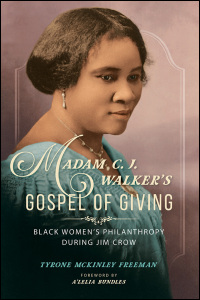

Tyrone McKinley Freeman, Madam C.J. Walker’s Gospel of Giving: Black Women’s Philanthropy During Jim Crow. University of Illinois Press, 2020. 304 pp.

Reviewed by D’Ann Campbell, Culver Stockton College

In our survey history classes, we discuss the differences between the robber barons and the captains of industry and base our assessment, in part, on what these white men did once they became millionaires. Did they decide to donate some of their newfound wealth to charity? Did they create and fund a university? Did they set up foundations to continue dispensing money for their pet projects after death? Were there strings attached to their philanthropy?

In our survey history classes, we discuss the differences between the robber barons and the captains of industry and base our assessment, in part, on what these white men did once they became millionaires. Did they decide to donate some of their newfound wealth to charity? Did they create and fund a university? Did they set up foundations to continue dispensing money for their pet projects after death? Were there strings attached to their philanthropy?

However, in the same period, there were a handful of women who became millionaires. Most inherited wealth from their husbands, such as Olivia Sage, but their giving patterns and wills were different from those of men. Madam C. J. Walker (1867-1919) was the first Black woman to create her own business, which enabled her to become “the first self-made female millionaire” (1). Historians have often discounted her pattern of giving because it was different from that of white people and seen as an exception to well-established rules. This six-chapter monograph of Madam Walker written by Tyrone McKinley, an assistant professor of philanthropic studies at Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, provides insight into “what counts as philanthropy” (ix) and why a close examination of Madam Walker’s pattern of philanthropy can provide us with a much richer, deeper, and broader understanding of philanthropy. McKinley based his study on historiography in terms of secondary sources and methods, as well as prodigious archival research. He argues that Madam Walker is typical of Black women’s philanthropy which began with the foundations of our country — not with the captains of industry in the late nineteenth century — and is going strong today. Challenging the common misconception that only white people are philanthropists, McKinley argues that Madam Walker “…became a significant American philanthropist and a foremother of [B]lack philanthropy today” (1).

Madam Walker (born Sarah Breedlove) has been the subject of countless biographies, articles, plays, songs, and even an excellent multi-episode documentary on Netflix. McKinley begins by summarizing what others have documented. As explained by McKinley, Sarah Breedlove was “Black. Female. Daughter of slaves. Orphan. Child laborer. Widowed young mother. Penniless migrant. Poor washerwoman. Philanthropist” (1). The story of her rise to success is nothing short of amazing. McKinley argues that Breedlove/Walker and the Black women surrounding her may have first received help and support from others. Still, as soon as possible and as much as possible, they began giving back to their communities, churches, and clubs.

Walker wanted to make a difference in the lives of average Black women, so she helped them get the education and jobs needed for them to become successful family breadwinners. She designed hair products for Black women, and when she settled in Indianapolis, her sales began to soar. As her product base expanded, she hired young Black women as salespeople and promoters.

While other studies of Walker have focused on her hair care empire, McKinley places her philanthropy at the center. Her philanthropy was much more than gifts to charities. She embodied the black women’s creed of volunteerism, giving of oneself too. As McKinley explains, “In the African American experience, philanthropy did not originate in wealth, but rather in resourceful efforts to meet social needs in the face of overwhelming societal constraints and impositions” (3). He clarifies, “It was less concerned with the exact form of gift giving than with the intent and appropriateness of the gift in responding to need” (3). He concludes, “As a result, African American philanthropy is better defined as a medley of beneficent acts and gifts that address someone’s needs or larger social purposes that arise from a collective consciousness and shared experience of humanity” (3-4). Therefore, Walker “did not create African American philanthropy, but she embodied [it]…” (9, emphasis in original). As McKinley later explained, “Her philanthropy emerged from four female networks and webs of affiliation that were grounded in collective consciousness and collaborative giving – washerwomen, churchwomen, clubwomen, and fraternal women – amid class distinctions” (192). As a result, McKinley concludes that “She was a significant American philanthropist whose giving thwarted Jim Crow in her day and changes the complexion and shape of generosity in ours” (199).

While others have utilized Walker’s will to illustrate her generosity, McKinley’s analysis of the document goes deeper. In the chapter on Walker’s legacy, McKinley explains that “Wills are not only legal documents but also personal stories and lasting legacies. They are personal narratives and direct instructions” (169). This point reminds me how our understanding of the history of the American West evolved a few decades ago because historians consulted women’s letters and diaries, which provided a much broader and deeper depiction of the role of families in opening and settling of the West. McKinley makes the critical point several times in his narrative that “One cannot study the history of African Americans without encountering their philanthropy; it is unfortunate that one can study the history of philanthropy without meaningfully encountering African Americans” (194, emphasis in the original). After McKinley’s study, I do not see how future historians of philanthropy in the United States could continue to exclude examinations of African American philanthropy.

January 3, 2022

how to join

Resources

about ccwh

We help women historians thrive through events, resources, and community.

Copyright © 2022 Coordinating Council for Women in History. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | site credit