Book Review – DRESSED FOR FREEDOM: THE FASHIONABLE POLITICS OF AMERICAN FEMINISM by Einav Rabinovitch-Fox

how to join

Resources

about ccwh

We help women historians thrive through events, resources, and community.

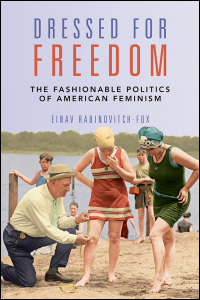

Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism. University of Illinois Press, 2021. 272 pp.

Reviewed by Jennifer Le Zotte, Assistant Professor of History, University of North Carolina Wilmington

Is fashion empowering or oppressive? The honest, difficult answer is yes. Einav Rabinovitch-Fox’s Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism centers on the recurrent puzzle of style and social progress by interrogating fashion’s role across the varied landscape of American feminism. Many of the trends examined are familiar, from bloomers to miniskirts, but the author’s assessment of their individual and collective significance is a welcome historical intervention. Well-organized and accessible, Dressed for Freedom fills in long-standing gaps in social movement, fashion, and feminist histories for all levels of interested readers.

Is fashion empowering or oppressive? The honest, difficult answer is yes. Einav Rabinovitch-Fox’s Dressed for Freedom: The Fashionable Politics of American Feminism centers on the recurrent puzzle of style and social progress by interrogating fashion’s role across the varied landscape of American feminism. Many of the trends examined are familiar, from bloomers to miniskirts, but the author’s assessment of their individual and collective significance is a welcome historical intervention. Well-organized and accessible, Dressed for Freedom fills in long-standing gaps in social movement, fashion, and feminist histories for all levels of interested readers.

Relying on industry archives, diverse media sources, activist speeches and letters, and formalized dress codes, the book surveys about eighty years of fashions relevant to American feminism. Rabinovitch-Fox’s primary focus is not on big “P” politics but on the extent to which intentionally liberating styles ripple out into the broader world as trends, carrying with them underpinning ideals. She argues that “fashion became a vehicle for the mainstreaming of feminism in public discourse” (5). Rabinovitch-Fox observes that diverse women’s desires for “fashionability” worked across race and, to a lesser extent, class more effectively than fashion itself (4). While not stretching historical actors’ intentions, the book convincingly shows how fashionable dress expanded civic rights for women.

“Feminism” has never been a singular movement. Therefore, Dressed for Freedom covers various sartorial perspectives: Black styles, queer fashions, and labor activist dress included. The author’s evidence and analyses are most robust when considering women’s fashionable purpose before the 1920s, concurrent with the first wave of feminism. Rabinovitch-Fox’s examination of the deceptively simple waist shirt (most popular in the decades before the passage of the 19th Amendment) competently demonstrates how fashion can unintentionally serve as an allying political force across racial and class divides. Though initially linked to the middle-class, white New Woman, the shirtwaist’s association with America made the garment a valuable tool of inclusion for immigrant, Black, and laboring women in the U.S.

Many of the fashion examples in Dressed for Freedom bear out the argument that liberating ideals piggybacked onto specific trends, such as the dress details of the iconic Gibson Girl and the shortened hemlines of the 1920s. However, this narrative wavers when Rabinovitch-Fox notes that the “mainstream fashion industry” appropriated the bosom-bearing hippie feminist style of the 1970s, “emptying it of any radical meaning” (179). At what point do the mechanisms of capitalism stop benefitting the spread of liberating ideology and start appropriating its aesthetic without the content? A more explicit representation of the changes in the “fashion industry” may be vital to answering this question.

Dressed for Freedom does assess U.S. women’s feminist interventions in the field of fashion design and distribution. Beginning in the 1920s, The Fashion Group, with its proponents’ skilled networking and lobbying, promoted American design internationally and enabled the individual prosperity of women in the U.S. According to Rabinovitch-Fox, by 1940, “nearly 84 percent of female executives in the United States (218 out of 260) held positions in a fashion-related field” (121). In later chapters, however, the use of “fashion industry” remains oblique. The author cites Women’s Wear Daily as the source of the controversial push for midi-length skirts in 1970, but the reader gets little idea of how and why individual boosters had the power they did. While investigating the intricacies of an expanding industry is delicate, complex work probably better suited to a stand-alone research project, the omission mystifies significant changes in how fashionability acts in conjunction with feminism after World War II.

As with any book that covers such a necessary and neglected topic as feminist dress in the U.S., Rabinovitch-Fox leaves meat on the table. For example, her riveting discussions of women’s wardrobes in wartime stay close to familiar material, such as the opportunities the Nazi occupation of Paris during WWII offered American designers and the expanding use of denim amongst female war workers. Still needing more in-depth consideration is the jumpsuit, a versatile and unisex World War I invention with a fascinating feminist history, as explored in a 2019 episode of the fashion podcast Dressed: The History of Fashion. Considering the role of female zoot suiters’ attire during WWII would include Latina dressers or the pachucas who asserted their own patriotic identity by emulating the pegged-leg and drape-coated vibes of their male counterparts and by wearing sexy styles with short skirts and fishnet pantyhose (Peiss 2014, 72). Ultimately, these further possibilities only underscore the need for the exciting and relevant discourse offered in Dressed for Freedom, which is appropriate for survey history courses and imperative for all historians of dress and fashion.

References

Calahan, April and Cassidy Zachary. Dressed: The History of Fashion. Podcast. https://dressedhistory.com/

Peiss, Kathy. 2014. Zoot Suit: The Enigmatic Career of an Extreme Style. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

August 19, 2023

how to join

Resources

about ccwh

We help women historians thrive through events, resources, and community.

Copyright © 2022 Coordinating Council for Women in History. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | site credit